I’m still recovering from the brutal jetlag of a Boston-Beijing flight, but I’ve spent my foggy-headed days and Ambien-infused nights thinking about my wonderful experience at a Harvard-sponsored medical education conference. While I was listening to lecture after lecture from Harvard’s top docs, surrounded by hundreds of primary care colleagues, I basked in the room’s positive, intellectual energy and rekindled my pride in my profession. I realized that I am extraordinarily lucky to be born in the U.S., and to be an American citizen and doctor — especially when I compare my job to my Chinese colleagues’.

I’m still recovering from the brutal jetlag of a Boston-Beijing flight, but I’ve spent my foggy-headed days and Ambien-infused nights thinking about my wonderful experience at a Harvard-sponsored medical education conference. While I was listening to lecture after lecture from Harvard’s top docs, surrounded by hundreds of primary care colleagues, I basked in the room’s positive, intellectual energy and rekindled my pride in my profession. I realized that I am extraordinarily lucky to be born in the U.S., and to be an American citizen and doctor — especially when I compare my job to my Chinese colleagues’.

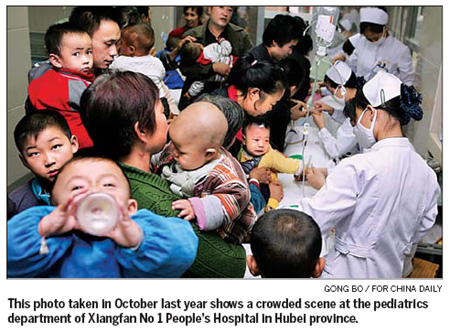

I recently had the unfortunate need to require some specialty medical care of my own, and I’ve been a patient a couple times at Tongren Hospital, one of China’s top eye hospitals. Tongren is exactly as I had envisioned — a madly crowded hospital full of countryside Chinese waiting in the hallways for days to get their 5-minute consult with what they’ve heard are the best eye doctors in China. Lines are long; people smoke in the halls and spit in trashcans. In the midst of all this normality, I had a first-rate eye exam by a cornea specialist, Dr Deng. She was very thorough, spoke good english, and helped me navigate the lines with ease.

It was — and is — impossible for me to encounter her and many of her physician colleagues without feeling acutely aware of how much better off is my life and my lifestyle. We are assuredly equally intelligent and motivated doctors, and yet just because of where we are born, I make magnitudes more than my Chinese colleagues. Not only that, but my daily job is far more rewarding as I see 25-30 patients maximum per day, while they would see 50-150 a day, or more — and there would still be hundreds outside their doors. Doesn’t sound very satisfying, does it? Well, it isn’t, and it’s demonstrated in many surveys here in China. There was a good review from China Daily (Doctors at receiving end in medical reform) discussing the high levels of stress and depression among Chinese doctors. And the Lancet recently had a great article also detailing the underlying perverse incentives in Chinese healthcare that have created frustrations for both doctors and their patients. Here are some highlights from the China Daily article:

Chinese physicians – referred to as “white wolves” by some due to their trademark white coats and reputation for profiting from prescriptions – are not a happy bunch. One in four suffers moderate to severe depression due to the stress of the job, according to a nationwide study by Peking University commissioned by the Ministry of Health…

So what is wrong with the medical profession?

According to health professionals, lawyers and academics, the key problems are an evaluation system that is based on a doctor’s ability to generate revenue for a hospital, a certification requirement that effectively prevents doctors from changing jobs and conflicting procedures for medical disputes that “encourage cover-ups”.

Of the more than 8,000 Chinese physicians polled – about 3,000 in cities and 5,000 in the countryside – as part of the Peking University study, most were 44 or younger, married and well educated.

“However, our research showed that the majority of doctors have a much higher degree of anxiety and depression than most citizens,” said Qiu Zeqi, a sociology professor who led the research published in October 2009. “They also have a very poor work attitude.”

The pressure on doctors comes partly from the way their performance is evaluated, said Zheng Shanhai, a doctor at China Meitan General Hospital in Beijing. “Money has become the major measurement,” he said. “Each section of a hospital has a different revenue target, and a doctor’s performance is evaluated monthly according to how much he helps to meet that target.”

Medics generate revenue through checkups and prescriptions they make out, which patients use to purchase drugs at the hospital’s pharmacy.

Doctors also charge a minimal service fee. In Beijing, patients pay about 5 yuan ($0.70) for an appointment – 4 yuan goes to the local government, 0.5 yuan to the hospital and 0.5 yuan to the doctor, said Chen Yan, a doctor specializing in respiratory medicine with Beijing’s China-Japan Friendship Hospital.

So, I am glad that healthcare reforms are taking place — in both my home country and here in China. I am very proud that Obama and his team have finally enacted into law the idea that universal healthcare is a right and not a privilege. And I’m very pleased that the bill strongly pushes for more preventive care as well as more primary care doctors. On this side of the ocean, I am very impressed by China’s recognition of their own challenges and their new laws to fix things. But it clearly will take decades before a Chinese doctor gets the same salary, lifestyle and respect that their foreign colleagues already earn. In this context, I feel a deep compassion and respect for my Chinese colleagues, as well as a heartfelt thanks for the enormous head start I was given just from my birthplace.

Follow me on Facebook: @BainbridgeBabaDoc

Photography: www.richardsaintcyr.com

Do you mind if i translate this article into Chinese and post it on my blog?

(http://cafe-carlis.blogspot.com)

Not at all! Please also have a link back to my website, thanks. I would love to have more of my articles translated for Chinese…